Summary Expressionism is commonly considered the story of white males flinging paint in New York Metropolis, the very definition of postwar American artwork. However the place are the Native Modernists? If the Tecolote Cave pictographs from 7300BC and Nineteenth-century Sioux girls’s ceremonial objects exhibit comparable geometry, chromatic restraint and spatial rhythm to that celebrated within the artwork of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, is American Modernism not indebted to Native artwork? A brand new exhibition of works by the Ojibwe summary painter George Morrison (1919-2000) at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Artwork might function a key to answering this vital query.

The artist’s largest present to this point, The Magical Metropolis: George Morrison’s New York (till 31 Could 2026), can be slightly intimate. With its 25 works on view, along with archival supplies, the exhibition phases a central rigidity in Native life: the town and the reservation—on this case, New York Metropolis and the Grand Portage Chippewa reservation on Lake Superior. However the phrase “strolling in two worlds”, which the historian Vine Deloria Jr derided for masking Native sovereignty’s fractures, hardly applies right here. (The title of the present comes from Morrison’s personal phrases: he known as New York a “magical metropolis”.)

Set up view of The Magical Metropolis: George Morrison’s New York on the Metropolitan Museum of Artwork Picture: Paul Lachenauer, courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Artwork, New York

Morrison’s Summary Expressionism flouts these cleavages with luxurious irony: lush, typically heat colors that idealise landscapes and concrete scenes whilst they expose the confrontational realities of displacement, prejudice and survival. Born into poverty on the Grand Portage reservation, by the point the artist moved to New York in 1943, he had already survived severed hair, cultural obliteration and tuberculosis—what worse might the town have to supply? His works’ titles alone reveal this duality: The Antagonist (1956) versus Autumn Nightfall, Crimson Rock Variation: Lake Superior Panorama (1986), gesturing between the bigoted and the bucolic, the city and the homeland. In Aureate Vertical (1958), the blindingly idyllic gleam of golden glass skyscrapers belie how the town streets can sweep the viewer below as swiftly because the squally waters of Morning Storm, Crimson Rock Variation: Lake Superior Panorama (1986).

Morrison belonged to a cohort of mercurial male Summary Expressionists lionised via the postwar “tortured genius” fable. He was shut with artists like Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, in addition to with Lois Dodd and Louise Nevelson. Unsurprisingly, self-destructive behaviour was solely tolerated alongside strict gender and racial traces. Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan and Morrison—who survived each crippling childhood sickness and an Indian boarding college—didn’t publicise or mythologise their very own psychological well being. The Victorian notion of hysteria pathologising girls and other people of color nonetheless continued.

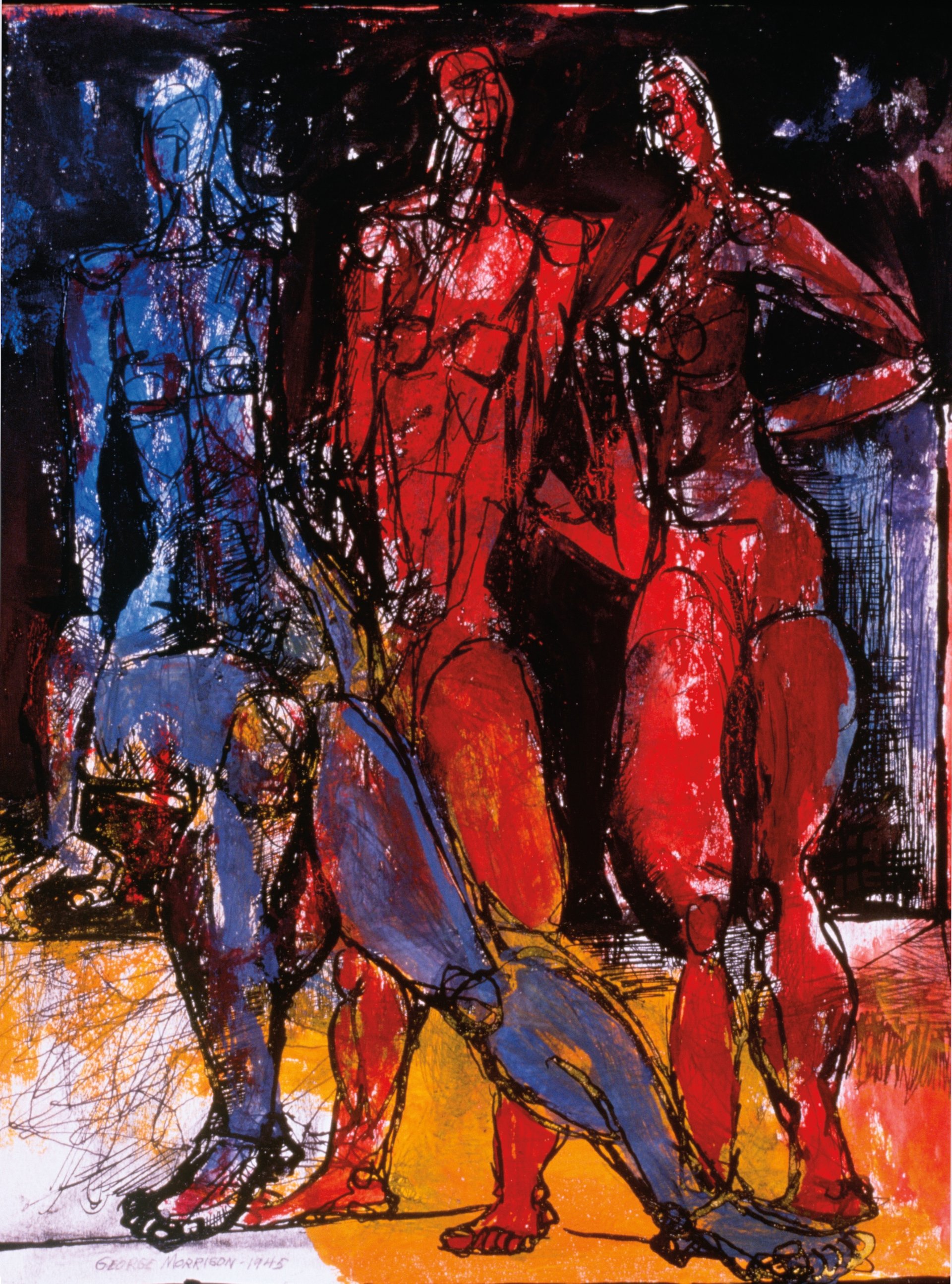

Morrison’s work exposes a quiet, complicated interiority resisting straightforward mythologising, however there’s a rugged, sultry edge beneath its floor. Although the artist was reserved in demeanor, his palette and topics betray a wealthy romantic and religious life. Three Figures (1945), for instance, deploys saturated figures in crimson and blue towards a darkish background to depict a risky love triangle he skilled whereas finding out on the Artwork College students League in New York.

George Morrison’s Three Figures (1945) Minnesota Museum of American Artwork, Saint Paul. © George Morrison Property

Morrison’s work has at all times been arresting. Willem de Kooning was so awed by what he noticed in a 1945 group present that he fell uncharacteristically silent. In Morrison’s first 5 years in New York, his work beguiled establishments too, travelling from the Whitney Museum of American Artwork to the Walker Artwork Heart in Minneapolis and Pennsylvania Academy of the High quality Arts in Philadelphia.

Morrison’s shift from illustration to gut-wrenched gesture might be seen within the watercolour-and-ink Dream of Calamity (1945), a distressed response to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The portray drew critics’ consideration with its disjunctive internet of traces and smoky dulled colors swirling over Japanese properties. Not like the works of many canonical Summary Expressionists, Morrison’s carried route: the lengthy horizon line, a distance simply out of attain. Maybe this was an escape from post-traumatic stress. The then-nascent metropolis remedy scene was too bourgeois to supply reduction. Morrison would as an alternative discover therapeutic via transformation—not of trauma, however of place.

George Morrison’s Dream of Calamity (1945) Tweed Museum of Artwork, College of Minnesota Duluth. © George Morrison Property

Take Structural Panorama (Freeway) (1952), for instance. The portray mutates the West Aspect Elevated Line (now the Excessive Line), turning a practice route right into a impartial geometry abutting a lush New Jersey waterfront with no river in between. Right here Morrison affords viewers the consolation of recognition—the West Aspect, the Holland Tunnel—but he employs a spatial technique eliding watery hues to make the verdant Backyard State seem intimate, inside attain. The land is there. The reality is there. Neither hidden nor spelled out.

Towards Morrison’s layered inwardness, his friends’ works really feel oddly hole. Pollock, Barnett Newman and Peter Busa stuffed their canvases with borrowed gestures from the very Native sources Morrison drew on, but they one way or the other produced glib facsimiles. The cultural vacancy of Morrison’s contemporaries mirrored a broader religious dislocation in non-Native America that, sadly, nonetheless exists at present.

George Morrison’s Structural Panorama (Freeway) (1952) Joslyn Artwork Museum, Omaha, Nebraska. © George Morrison Property

Although Morrison realized classical methods, he moved in direction of abstraction—maybe to transcend the confines of realism in life and portray. Imbuing emotion into every stroke and line with mathematical precision, Morrison depicts landscapes from the Huge Apple to Chippewa territory, drawing shockingly clear visible and ontological traces with each natural and engineered horizons. (In spite of everything, the whole lot within the metropolis, even the metal and glass of the Empire State Constructing, originated in nature.)

However Native artwork nonetheless stays sidelined—separated from the Modernist canon it helped form, too typically confined to remoted museum wings and galleries. Regardless of many years of progress and intermittent visibility, Native artwork’s full recognition stays a piece in progress. Even with the Morrison exhibition, the present’s placement within the American Wing—abutting the Met’s Native assortment slightly than amongst Morrison’s white contemporaries—suggests the institutional challenges that the curator Patricia Marroquin Norby navigated in securing parity for the artist. The Met’s placement exposes a persistent fiction: that up to date Native artwork belongs to historical past, not the current.

The Magical Metropolis: George Morrison’s New York, Metropolitan Museum of Artwork, New York, till 31 Could 2026